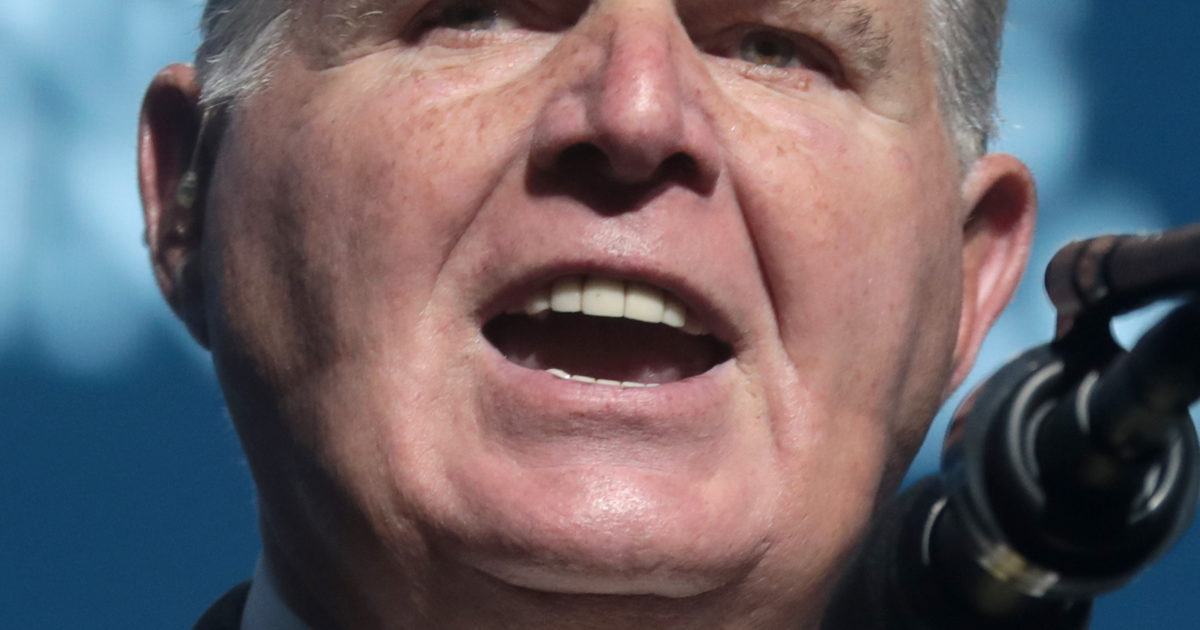

The American right is mourning the loss of Rush Limbaugh today. The iconic broadcaster has been a Republican icon for decades and was the creator of the talk radio industry as we know it today. While the right mourns, some on the left are celebrating the death of someone they saw as a villain. The truth is much more complex.

Although I hadn’t listened to Rush much in years, I once considered myself a “Dittohead.” When I remember first listening to him as a college student in the 1990s, it wasn’t so much that Rush told me what to think as that I heard him and said to myself, “Hey, this is the same stuff I believe!”

Although I didn’t listen often over the past decade or so, Rush’s show was ubiquitous, even after three decades. In the radio market where I live, there are about three conservative talk stations, and from noon to three, they all aired Rush Limbaugh.

I didn’t know Rush personally as many other conservative commentators did. That allows me to talk about the man and his legacy with a bit more objectivity than many of the other people that you’ll hear from over the next few days.

Rush’s greatest contribution to conservatism was in making it accessible at the grassroots level. Prior to the debut of the “Rush Limbaugh Show,” conservative thought was mainly the province of newspapers and magazines. Columnists like Willam F. Buckley and Charles Krauthammer were giant conservative intellects, but because few Americans read National Review or the Washington Post, their reach was limited.

Then along came Rush.

It wasn’t just Rush’s talent that enabled his show to succeed, it was the FCC under the Reagan Administration. Prior to 1987, the FCC enforced “the fairness doctrine,” a policy that required broadcast stations to provide equal time to opposing viewpoints. It is no coincidence that Limbaugh’s show debuted and took off in July 1988. (Knowing this, it’s ironic that many on the right want to re-introduce some form of fairness doctrine to both mainstream and social media). Suddenly, conservative politics were accessible to the masses, and many, as I did, said, “This guy makes sense.”

That was the upside to Rush’s success. The downside is that his success helped turn politics into entertainment and spawned many copycats. To distinguish themselves from Rush, many of these talkers had to become more outlandish and radical. The “shock jock” was born and pushed the boundaries of the envelope.

CNN and the birth of the 24-hour news cycle in 1980 have often been credited with beginning the news-as-entertainment and news-addiction phenomena in America, but conservative talk radio had a lot to do with it as well. If you have three hours of airtime to fill every day, you have to find something to talk about. Even if nothing of consequence is going on, you still have three hours to fill.

What the conservative talkers learned was that outrage sells. This realization led to what I call the “outrage du jour.” The industry scours the country for outrageous stories about liberals and leftists and then gives them national attention. You would have never heard about the latest liberal school board action in Podunk, Iowa or leftist city council resolution in BFE, Minnesota and they don’t affect you, but, by George, you know about them now and you’re outraged about them! What’s more, you assume that radical stupidity in one corner of the country is representative of liberals throughout the country.

Ben Shapiro is a good example of this phenomenon. I used to listen to Ben regularly when he discussed the news, but his show has devolved into an hour-long rant against some obscure article that no one else has ever heard of. On the rare occasions when I listen to Ben these days, most often because I’m curious about his take on some big news story, I usually find that the big event might get a couple of minutes of discussion, and then he returns to attacking the media.

And the left does the same thing. A favorite game of both sides is to focus on the most idiotic and radical examples of the opposition that they can find and then apply that example to everyone on the other side. The tactic leads us to stereotype our political opponents as bad people and undermines our ability to compromise and come together.

This national division and outrage culture is a direct result of the growth of political entertainment and the need to one-up other hosts. This all started with Rush Limbaugh, but in fairness, if Rush hadn’t done it someone else would have. I’m not sure we’d be better off with Howard Stern or Michael Savage as the father of conservative talk radio.

My own split with Limbaugh came as Rush grew into a big backer of Ted Cruz. By giving a platform to Cruz’s intraparty warfare, I see Limbaugh as one of the architects of the current Republican crackup. I’ve pointed out before how John Boehner and Mitch McConnell were much better political strategists than Ted Cruz, but Rush and the radio talkers were all-in on Cruz, even after the abortive and disastrous 2013 government shutdown.

It was Limbaugh and the others who convinced the Republican base that they were betrayed by RINOs in an attempt to coronate Cruz as the 2016 nominee. (They also kept the border open by undermining attempts to create a bipartisan solution at immigration reform.) Limbaugh was among those who sold the idea of Donald Trump as a conservative savior and whitewashed Trump’s many problems, which eventually paved the way for Joe Biden’s victory, the Democratic takeover of both houses of Congress, and the brewing Republican civil war that we have today.

By most accounts, Rush Limbaugh was a nice person and many people will speak of him in glowing terms, but his legacy is much more complicated. Rush made the conservative ideology and politics accessible to the average American, which is a good thing, but he also contributed to our national division and helped lead the Republican Party down the dead-end road of Trumpism to a possible split that would leave the Democrats ascendant.

Rush’s journey is closely linked to the journey of the Republican Party through the post-Reagan years as it moved from a party based on conservative principles to one that was based on opposition to Obama, and finally, to a party that is now focused on following celebrity politicians. Rush Limbaugh was not the sole factor in that metamorphosis, but, for better or worse, he was central to the change.

Follow David Thornton on Twitter (@captainkudzu) and Facebook

The First TV contributor network is a place for vibrant thought and ideas. Opinions expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of The First or The First TV. We want to foster dialogue, create conversation, and debate ideas. See something you like or don’t like? Reach out to the author or to us at ideas@thefirsttv.com.