“I was never taught that I might potentially have serious mental problems, emotional problems, and social problems when I got out,” wrote a former prisoner who spent a dozen years inside.

No one helped me learn the language of a 35 year old adult male. They literally are setting people up for failure by sending them out in the world without at least a warning that you may potentially have some serious side effects from being exposed to violence, correctional officer abuse, brutality, corruption and apathy, a constant feeling of unease and a lack of safety, and from waking up with an overwhelming sense of dread everyday for over a decade. Not even a simple pamphlet of what you’re mental health language and options are.

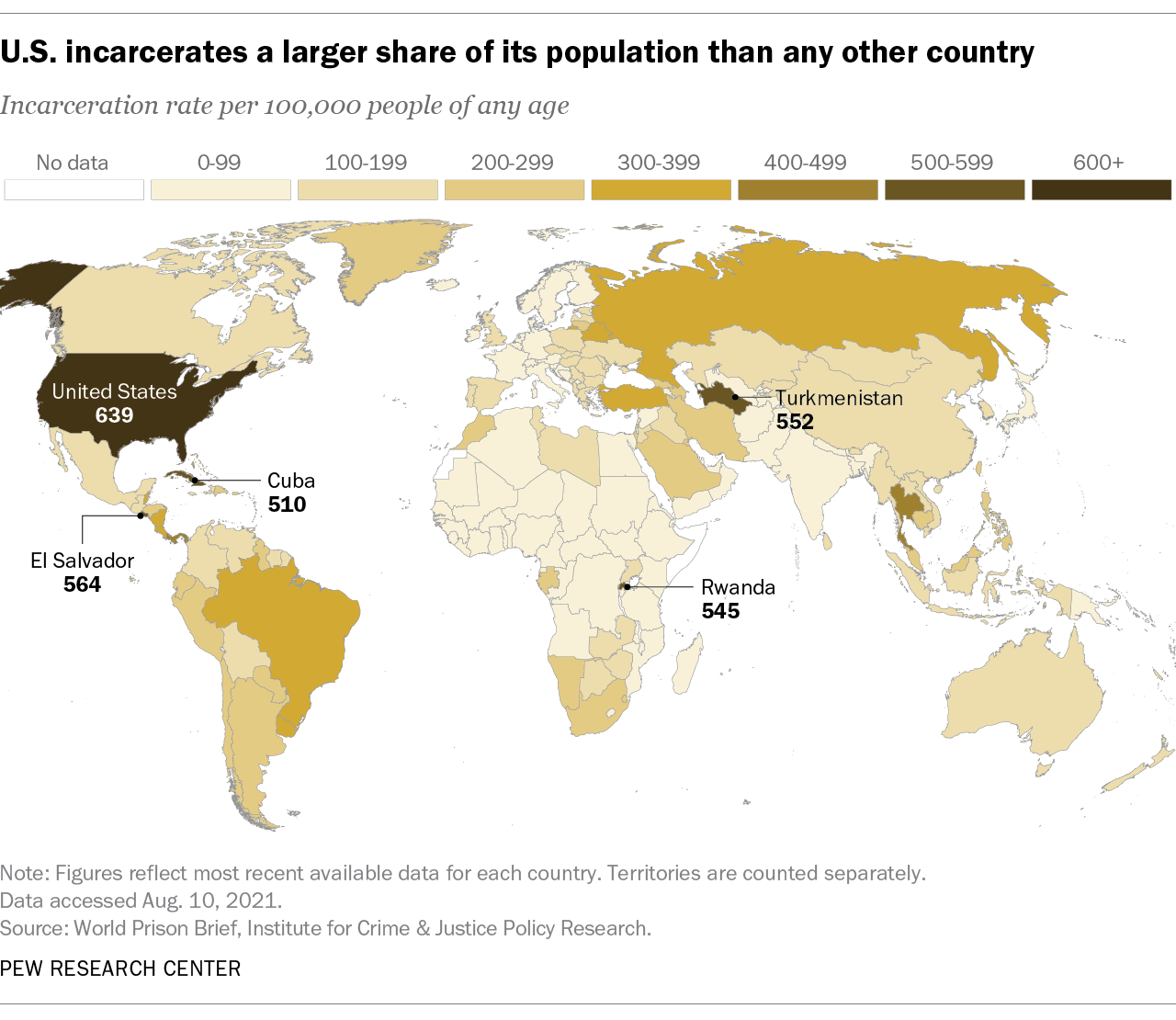

Prison is a brutal, racist, violent place that gnaws that the souls of those who live or work inside. Spending any amount of time in prison has a profound negative mental affect on individuals. Then those people are let out, and expected to live “normal” lives. And the problem is growing rapidly as incarceration rates fall and more prisoners are released. A Pew Research paper noted that “despite these downward trends, the U.S. still has the highest incarceration rate in the world,” as a share of population.

In Massachusetts, the Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division found after an investigation that “there is reason to believe that the conditions violate the Eighth Amendment of the Constitution” in a November 2020 release.

“Our investigation revealed that MDOC fails to provide adequate mental health treatment to prisoners experiencing a mental health crisis and instead exposes them to conditions that harm them or place them at serious risk of harm,” said Assistant Attorney General Eric Dreiband for the Civil Rights Division. “Remedying these deficiencies promptly will ensure that we protect the constitutional rights of these vulnerable prisoners and promote public safety.”

Prisons typically hire correctional officers whose career goals might have been in law enforcement, but for some reason failed to land—or keep—a job in policing. They typically get less respect (or none) than other law enforcement, and their own crimes dot the headlines of newspapers around the country.

There’s a “wall of shame” inside Georgia prisons—I’ve seen it with my own eyes—that features all the correctional officers who have been arrested for various crimes, including prisoner abuse and contraband. In July, Atlanta 11Alive television news published a video revealing DOC’s actions during large riot at Ware State Prison.

Many COs have their own mental health problems. In Warner Robins, Georgia (where I lived for nearly 26 years), Anthony Rawls, a lieutenant at Macon State Prison, was killed by police in 2013 after threatening to kill his wife.

At least COs can leave the profession, if they don’t end up behind bars themselves. Prisoners really don’t have a choice over when they’re released, except I suppose to commit a crime behind bars to stay in. But ask any prisoner inside, and you’ll find 100 out of 100 would rather be released. That is, until they hit the real world outside and find out how prison has permanently damaged them, mentally and emotionally.

Former federal prisoner Charlotte Garnes told the Savannah Morning News that “the system wants to see that you’re contributing. They set you up to fail. They keep you enslaved in the system.” She lost her job after a judge denied her request for early probation termination. When the federal government informed her employer of the denial, they fired her from a job she actually enjoyed.

“While incarcerated, I dealt with depression, I dealt with grief, I dealt with loss from my mom getting sick to my stepfather dying,” Garnes said. “Nothing was provided for me. And when you get out of prison, you have all that trauma and you don’t have the mental support around. My question is: when do people expect you to work through it?”

When? They don’t.

In August of 2020, Gov. Brian Kemp signed legislation allowing some rehabilitated inmates to request courts to expunge certain misdemeanors from their record, as long as they stay clean. It’s one step, but Georgia has the dubious honor of having one of the highest incarceration rates in the nation. We lock up a lot of people for a lot of crimes, and in prison they don’t learn to be good citizens. When they get out, all that baggage comes with them.

Read the whole article in the Savannah Morning News. Also read James Morrissey’s answer on Quora to the question“what should the public know about prison life to drive meaningful reform?” [It’s got some NSFW language.]

People who are long-term incarcerated then released back into society, even if they get some college classes or shop time inside, are not prepared mentally, emotionally, and financially, to be released. These people become a mental health burden on communities where they live, and many times revert back to crime.

Our probation and court system are not set up to deal with these issues. They see their jobs as keeping the inmates (they’re released but from the point of view of parole officers, they may as well not be) from harming anyone else, and following the rules or being locked up again.

I don’t have the answer here, but I do think in the midst of a pandemic, and a massive crime wave, we will have to come to terms with these issues in the near-term versus the long term. Building more prisons and locking up more people is not the answer. All that does is make the wall of shame grow.

Follow Steve on Twitter @stevengberman.

The First TV contributor network is a place for vibrant thought and ideas. Opinions expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of The First or The First TV. We want to foster dialogue, create conversation, and debate ideas. See something you like or don’t like? Reach out to the author or to us at ideas@thefirsttv.com.