President Trump and many of his disciples were banned from social media. This has opened up a First Amendment can of worms with many of his supporters complaining about censorship and the alleged dangers of a slippery slope.

While I do have some sympathy for the slippery slope argument, the First Amendment and censorship complaints are off base. There are freedom of speech issues with the bans, but they do no relate to the First Amendment.

The reason is that the First Amendment does not apply is that the Constitution constrains the government, not individuals or private businesses. Think about the actual text of the First Amendment and not just the fuzzy concept of free speech:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

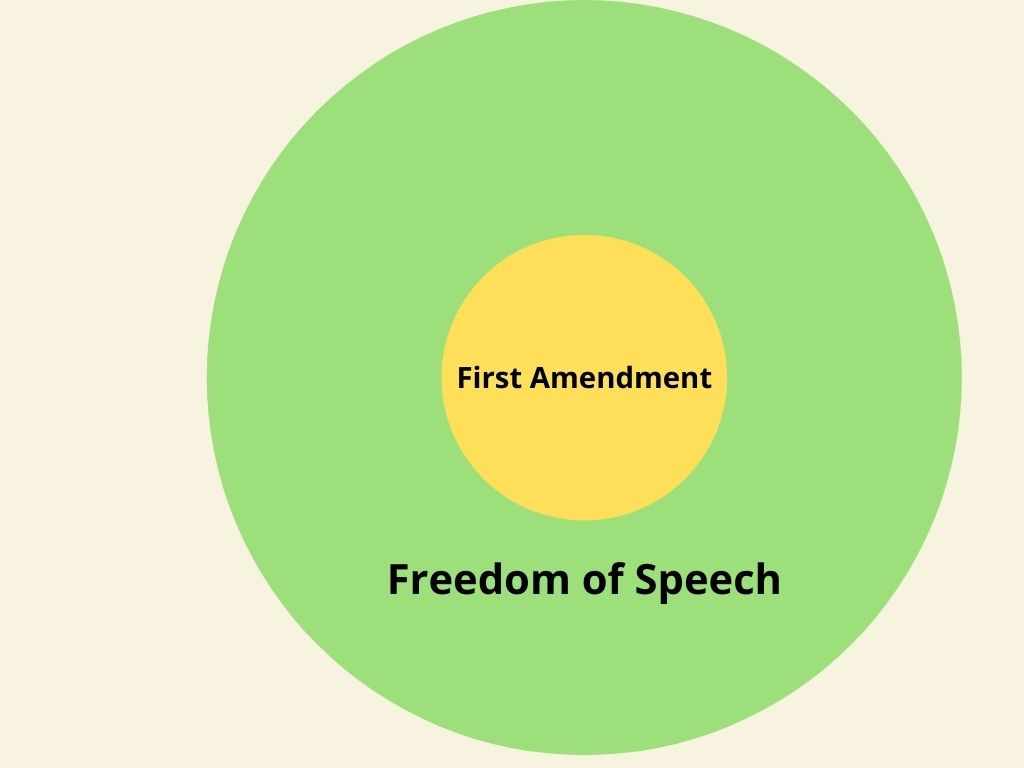

The phrase, “Congress shall make no law,” is key. The First Amendment does not prevent private establishments from making their own rules about speech and conduct. To illustrate this concept, consider the Venn diagram below. Freedom of speech is a very broad concept while the First Amendment regulates the small, defined area of government abridgment of speech.

That being said, there is still the question of free speech and whether social media companies can and should ban Donald Trump and his minions. The question of whether they are allowed to do so is a resounding “yes.” Congress would be abridging the First Amendment rights of social media companies if it imposed its own speech rules on them.

Back in October, I took a detailed look at Section 230. It turned out that Section 230 doesn’t say what most people think it does. The law essentially gives social media companies the right to set their own standards and enforce them without facing civil liability.

This does not confer special rights on social media companies. Instead, it gives social media companies, which are private businesses, the same rights as brick-and-mortar businesses to control behavior on their own turf.

As an example, think about a protester who wants to alert the public to the dangers of the lizard people who live in our midst. Our alarmist can stand in the public square and yell about lizard people, but if he tries to go into a private store to warn the customers inside, the owner is within his rights to throw him out if he doesn’t behave.

It’s the same with social media. If users don’t follow the rules then they can face the consequences of being thrown out.

I do agree that social media companies occasionally make bad calls, but the bottom line is that the call is theirs to make. I say that the conservative response to these bad calls should be to use the power of the marketplace and the freedom of association. Complaints about unfair bans have led to the reinstatement of some accounts that were wrongly banned. If a user isn’t happy with Twitter or Facebook’s actions, there is always Parler or some other platform.

The argument that access to social media is a right is more of a leftist argument than a conservative one. Claiming a right to access a private social media platform is really no different than claiming that a baker has a duty to bake a cake for a gay wedding, that healthcare is a human right, or that one person’s wealth belongs to us all. All four arguments boil down to the claim that you have the right to the fruits of someone else’s labor.

Overwrought comparisons to Chinese censorship also miss the boat entirely. Shay Khatiri had an excellent point on Twitter. In China, the government censors the people of the country. What Republicans are now arguing for, requiring private companies to give the president a platform and a megaphone, is closer to the Chinese model than allowing companies the freedom to turn the president off.

Pleading for government regulation of private business relationships is not a conservative solution. In my opinion, expanding government into private life should always be a course of last resort, but asking for regulation as a Democratic president and Congress take the reins strikes me as a particularly bad idea.

And let’s be honest, not all government restrictions on free speech are illegal. If our lizard-man conspiracy believer stands in the park and yells his warnings, he might be subjected to a noise complaint, for instance. The classic test for government limitations on speech comes from Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes’s opinion in Schenk v. United States that “falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic” is not protected speech. That’s pretty close to where we are today.

For the past two months, Donald Trump, Mike Flynn, Lin Wood, Sidney Powell, and others have been perpetuating false claims that the election was stolen. (That these claims are false is not an opinion. They have been unable to support their allegations with evidence that stands up in court. These defeats were not all on standing or technicalities. Several were rejected on the merits.) These claims were intended to overturn the election and some blatantly provoked violence. There is a direct line between these claims and this week’s insurrection at the Capitol.

There’s a pretty strong case to be made that the social media platforms not only had a right to ban these people but that they had a duty to do so in order to prevent their sites from being used to foment a violent insurrection and overthrow of the federal government. If Twitter had enforced its rules with regard to the president’s tweets long before this week, the attack on the Capitol by domestic terrorists might never have happened. If there was government regulation of internet speech, these accounts might have still been banned to avoid inciting further uprisings.

What the issue boils down to is responsibility. I believe that people, and especially public figures, have a duty to act responsibly and not incite mobs, especially on false pretenses. If people do not act responsibly, then businesses have the right to enforce rules that take away their social access.

In the end, access to a private social media platform is a privilege, not a right. You have the right to speak, but you do not have a right to post on a private platform. You do not have the right to require that businesses give you a megaphone. You have the right to speak but not the right to be heard.

Freedom of speech does not guarantee a freedom to tweet.

Follow David Thornton on Twitter (@captainkudzu) and Facebook

The First TV contributor network is a place for vibrant thought and ideas. Opinions expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of The First or The First TV. We want to foster dialogue, create conversation, and debate ideas. See something you like or don’t like? Reach out to the author or to us at ideas@thefirsttv.com.